Omar Memišević

Click here for the article in B/C/M/S

I was closely involved in compiling data on Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) for the GEO-POWER-EU Interdependence Database recently launched by the GEO-POWER-EU research consortium. The aim of the database is to provide data on a number of social, economic, security and political issues in order to better understand how nine countries (the Western Balkans 6, and the Eastern Partnership, consisting of Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia) engage with five different geopolitical actors: the EU, the US, China, Russia and Türkiye. While the first iteration of the database is now available for public use, the experience in data identification and collection has itself been a dynamic and a challenging one.

One of the biggest challenges in identifying data for the database is the inherent lack of available data for a large number of the indicators, amplified by the convoluted institutional framework of BiH, which makes identification of relevant stakeholders and depositories challenging. This is perhaps the biggest difference between BiH and the other countries being studied, and something pointed out by the Venice Commission nearly two decades ago in 2005.

One example of a lack of available data is the “Number of employees in diplomatic missions” in the 2007-2024 timeframe. This is included in the database to provide a data point that can contribute to understanding the extent of interest in and engagement in one country by another over time, specifically since 2007. The reason why this was challenging is quite simple: there is not a single person in the MFA who has the relevant documents that show the number of employees for 2007, as confirmed by an official in the Bosnian state-level institutions.

This suggests several things. First, data which should be archived somewhere in the institutional databases is not archived, and there is a lack of systemic approach to the digitalization of such documents. Despite foreign efforts at mitigating this, such as the 2020-2026 UNDP-led project “Digital transformation in Bosnia and Herzegovina”, it remains clear that strengthening state level institutions is not a priority of certain political actors.

Second, there is a chronic lack of human resource capacity within some institutions in the country when it comes to data collection and provision that may be sought through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. If this kind of record keeping and archiving is not being done now, it is reasonable to wonder about the capacity of the country to do this systematically during the EU accession process, and potentially in the future if a member.

Third, and on a related point, a researcher or any interested citizen will encounter a myriad of other challenges related to archiving, accessibility and systemization, not to mention the reality that finding civil servants prepared to assist with such information provision is often unpredictable.

These three impediments are not limited to this particular indicator and the capacity of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but also to other institutions that should be tracking and archiving data taken for granted in many other countries.

While data collection for BiH was in some cases challenging, the fact that data was eventually assembled and systematized will provide future researchers, policymakers, and BiH citizens with foundations from which to build. The long-term orientation of the project and its data-driven approach to geopolitical research and analysis could over the next two years indicate a roadmap for more effective data collection and citizen accessibility. As just a few examples, the following caught my attention as I have long been a student of issues related to security and security cooperation.

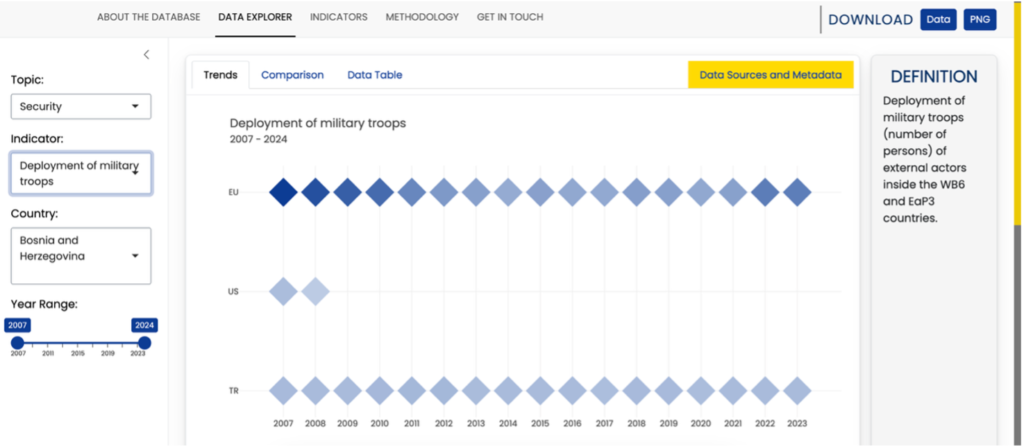

One example is illustrated below, which highlights the number of peacekeeping troops in the country:

The source of this information included local media outlets and official policy documents from EUFOR contingent contributing states. It highlights a gradual increase of EUFOR troops stationed in the country, as part of Operation Althea, an EU peace enforcement mission tasked with ensuring a “safe and secure environment,” in Annex 1A of the Dayton Peace Agreement, operated under Berlin-plus arrangements for NATO support. Several non-EU member states contribute forces, with the largest contingent of these coming from Türkiye. From 2010 onward, the number of soldiers, as well as countries involved, diminished to a low of roughly 600 troops, even as politically driven frictions escalated to a high in late 2021/early 2022. This remained the case until Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, when EUFOR was effectively doubled. It is now roughly three times its force levels four years ago. (Ex. 1. Increase in Op. Althea troops – depicted below). What may seem to be boring or bureaucratic data points actually contributes to an important story.

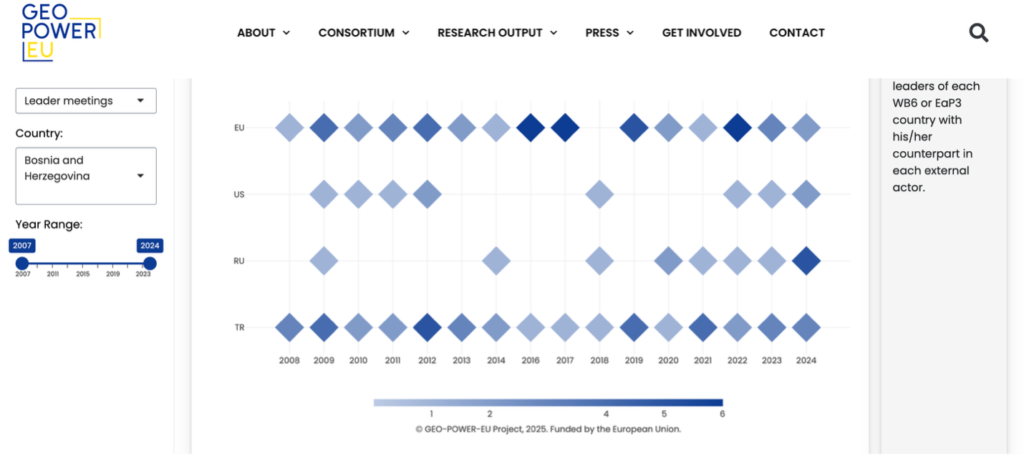

Another trend that caught my eye is illustrated in the chart below:

This visualizes a period of relative international isolation between 2012 and 2022, during which very little progress was made on the EU, or NATO, integration path, while at the same time, BiH officials had very few visits from international actors to the country. This corresponds to a period of time of general heightened tensions among local political actors, including divisive and secessionist rhetoric coming from Republika Srpska (RS), one of the two entities within BiH, as well as several election results not fully implemented due to political deadlock. The result of this domestic dysfunction was corresponding international dysfunction.

There is always a reason to be wary of telling a story through purely quantifiable data. However together with qualitative insights and analysis Data that is properly collected and archived overtime can contribute to not only an understanding of recent history but the current day. The GEO-POWER-EU interdependence database provides valuable insight into BiH, both by bringing together available information, while also demonstrating significant data and data access gaps. Filling these gaps, ensuring citizen access to data that should be publicly available, and ensuring that both policy makers and independent analysts can contribute to Data driven decision-making should be seen as a priority not only for the institutions of BiH, but for the European Union and its member states who claim to want the country to have an EU membership perspective.

This was funded by the European Union’s H2020 Research and Innovation program under grant agreement #101132692 – GEO-POWER-EU – HORIZON-CL2-2023-DEMOCRACY-01