Summary: The GEO-POWER-EU Interdependence Database [1] reinforces the qualitative conclusion that the EU has significant potential leverage in Serbia – and in the rest of the Western Balkans – in comparison with various geopolitical challengers. However, this leverage remains largely unused, and represents a missed opportunity in terms of the EU’s geopolitical interests, a more assertive enlargement policy or general promotion of the EU’s own declared values.

European Council President António Costa made a speech on May 13 during his scheduled visit to Belgrade, which was on the surface unremarkable; the well-worn, “industry standard” talking points of EU institutions. However, it was the context that made Costa’s remarks sound remarkably off-key to anyone who understands the current dynamics in Serbia and the Western Balkans as a whole – including the people who live there. Borrowing a term first heard by the authors in this context two years ago, people feel like the victims of a campaign of gaslighting.

First, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, whom Costa affectionately addressed more than once as “Dear Aleksandar,” had just returned from a May 9 Victory Day parade in Moscow with indicted war criminal Vladimir Putin, despite repeated warnings from EU officials.

Furthermore, Costa visited a Serbia in which a student-led movement has been demanding accountability and justice for 16 needless deaths in the November 1, 2024 Novi Sad railway station roof collapse, also calling for an end to the endemic corruption and state capture attributed to Vučić and his long-dominant and responsible coalition. The EU has generally pretended not to hear these voices or demands, despite the fact that Enlargement Commissioner Marta Kos stated that they were consonant with the country’s standing reform obligations as a candidate. There were no reports of Costa lovingly showing support for Serbia’s “dear youth.”

While baffling and discouraging to hundreds of thousands of Serbian citizens, the EU often acts as if it had no leverage over Serbia. Yet the data from the GEO-POWER-EU Interdependence Database show otherwise, leading to reasonable questions about the EU’s betrayal of the very values its members should preserve and promote.

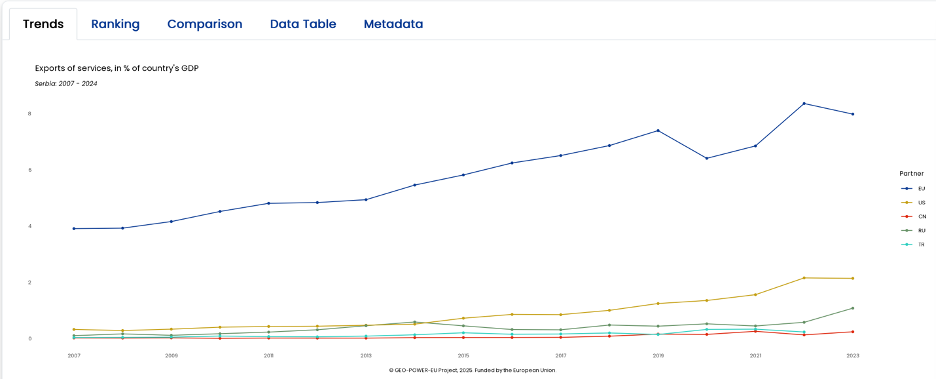

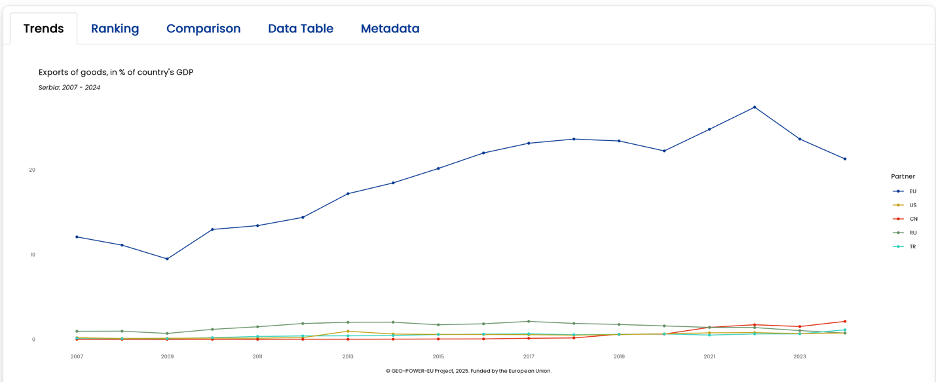

A quick visual shows that Serbia’s economic relationship with the EU far exceeds that with other geopolitical options, in terms of exports of goods and services:

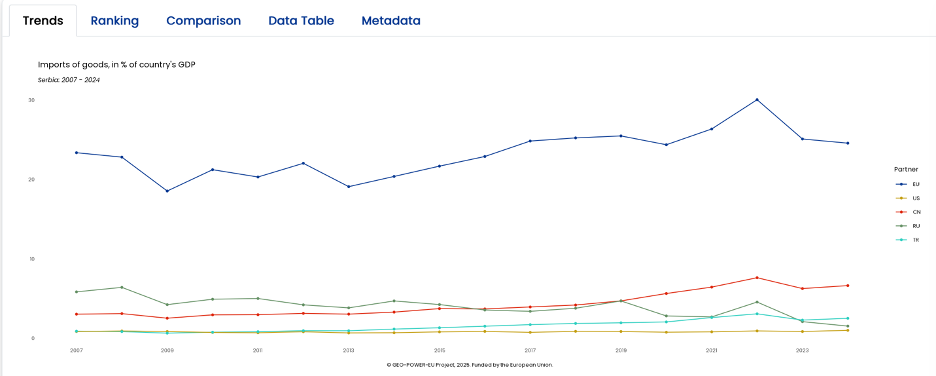

…. as well as import of goods:

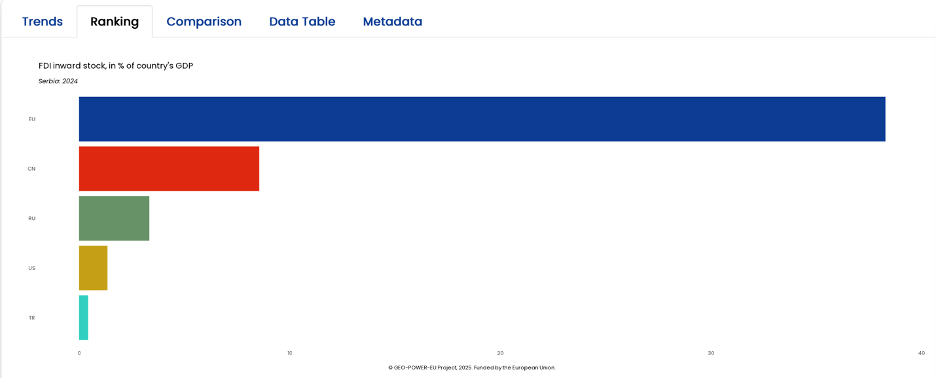

There is a similar dominance in terms of FDI:

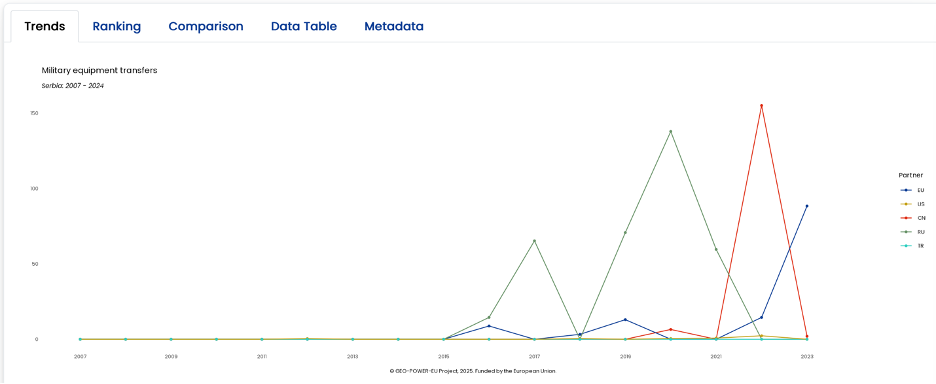

While economically Serbia’s ties to the EU are clear and dominant, there is more evident geopolitical diversity on other measures, with Russia and China making some significant arms transfers, for example:

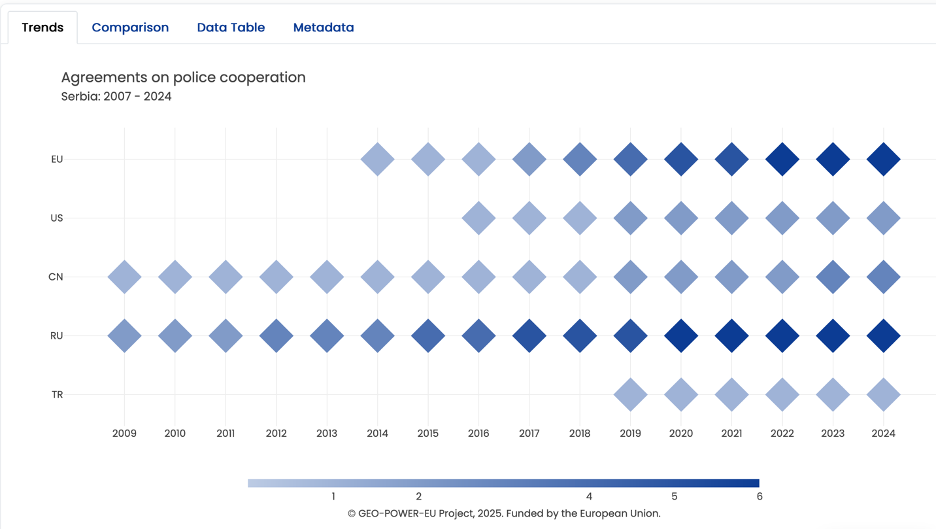

And those same countries demonstrating a continuing interest in police cooperation:

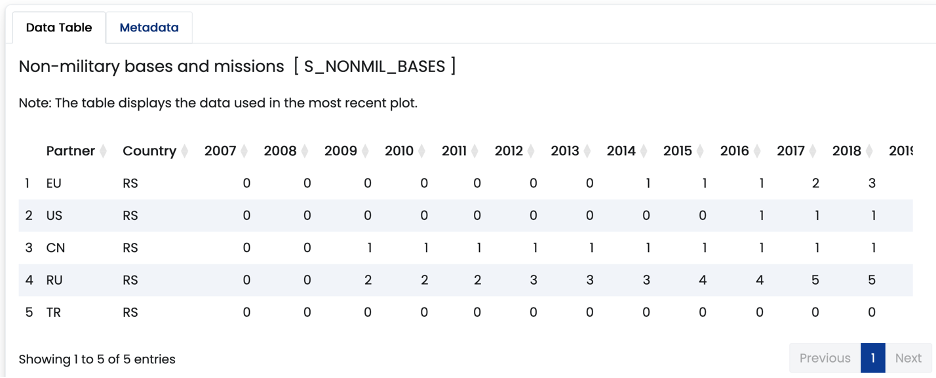

There has also been a consistent interest in physical presence, particularly by Russia:

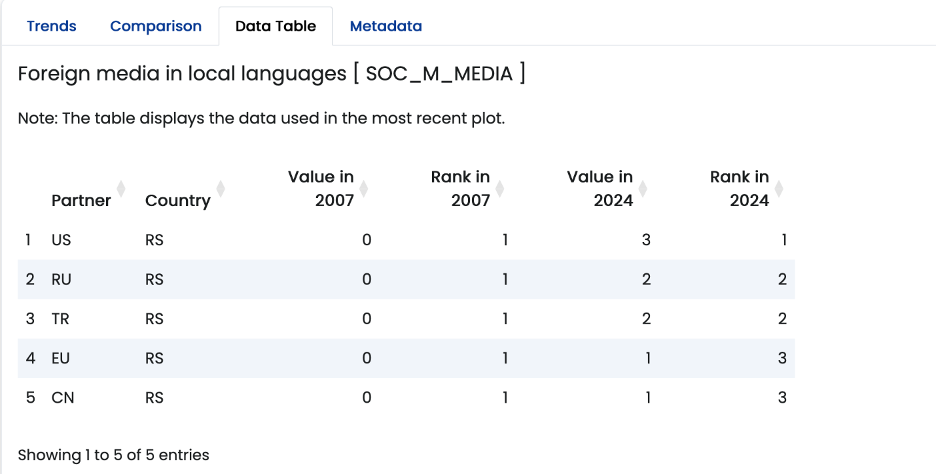

In addition to this security sector presence, Russia has also demonstrated an interest in media penetration, which is consistent with its interest in shaping narratives in general, and plugging into longstanding claims of cultural affinities:

(It bears noting that as the US has indicated an interest in reducing or completely eliminating media engagement, these numbers are likely to change in the next 1-2 years.)

The database enables a view of many other indicators. However, the picture that emerges allows a few conclusions to be made. At the most basic level, it is clear that Serbia is continuing a long tradition of diverse relationships towards both the west and the east: “sitting on two chairs.” While the economic chair is firmly anchored by the EU, on important issues of security and cultural influence, there is more diversity, and more willingness to engage with “the east,” including with partners that are illiberal and authoritarian.

These trends should concern Brussels. If Serbia is seen as a credible candidate for membership, the more it builds its security sector with help or encouragement from actors such as Russia and China, the more difficult it could be to align its security practices and policies with the EU. Similarly, influence operations by Russia in Serbia – through direct official interaction, the media, cultural activities etc. – aimed at shaping public opinion and supporting public political narratives will have an impact on a population that has already lost faith in the idea of an EU-oriented future.

Furthermore, these trends show that in the void of applying its potential leverage against authoritarian adversaries (Russia, China, but also Turkey and Gulf State absolute monarchies), those challengers have gained unnerving footholds in the country’s economic, political, social, and security spheres. This traction is amplified by the EU sidelining its own values allies in Serbian society now illustrated by half a year of effective policy inertia. Meanwhile, the erratic changes in US foreign policy, as ideas about comprehensive security and the value of the trans-Atlantic alliance are being scuppered in favor of raw short-term transactionalism, create further space for anti-democratic foreign influence.

While the EU’s relative position competing with geopolitical challengers declined, even since Commission President Ursula von der Leyen launched her first term in 2019 by proclaiming an aim to assemble a “geopolitical Commission,” it still outmatches competitors across a host of key indicators, as well as maintaining advantages of geography and societal/cultural links. The EU needs to apply this leverage in service of its foundational values, in alliance with Serbian citizens who have demonstrated that they share them and want EU support, to have a hope of achieving enlargement, including by “selling” it to its own citizens. Supporting the values being expressed clearly by Serbia’s citizens could then serve as a catalyst for a new values-based approach to the other countries in the Western Balkans. The database shows the EU some of its tools. But only political vision and will to shift policy will bring their effective application.

[1] Disclaimer: This article draws on data from the GEO-POWER-EU INTERDEPENDENCE DATABASE (2025) to examine EU leverage and authoritarian influence in Serbia, in combination with current political developments.

This was funded by the European Union’s H2020 Research and Innovation program under grant agreement #101132692 – GEO-POWER-EU – HORIZON-CL2-2023-DEMOCRACY-01