Majority Voting as a Catalyst of Populism: Preferential Decision-making for an Inclusive Democracy, by Peter Emerson, Springer, 2020

I first met Peter over 20 years ago at what was then an annual summer conference on the topic of democracy and human rights in multiethnic societies, in the small town of Konjic, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Those were optimistic times, as in those first post-war years there was both still the palpable relief that the 3 ½ year war in Bosnia had come to an end, and a sense that life for people – and for the country – was getting better. The conference was a small part of that era, organized by a Bosnian professor who had moved to Norway during the war, but who was committed to bringing scholars and students from around the world to learn from the lessons of the violent tearing apart of Yugoslavia, to be a part of the charting of a new, more peaceful path forward. There was a genuine enthusiasm among that generation, a still-held belief that human rights were not only universal, but contributed to peace and human security; and a sense that spreading liberal values globally was a good thing.

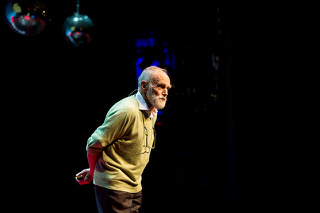

Peter had been in parts of Bosnia during the war, and, drawing on his own experience coming from a “mixed marriage” in Belfast, Northern Ireland, had a special perspective. As he travelled Europe and the world on his portable bicycle, he was well-placed to speak to the futility of violent conflict, the predatory nature of opportunistic politicians and elites manipulating public fears and differences to create “us vs. them” realities, and the need for broad-based citizen participation in public life to push back against this unfortunate political reality. He had been posted to Derventa – a town in northern Bosnia ethnically cleansed at the outset of the war – as an observer in the first post-war election in autumn 1996. The elections were aimed at being a step towards “normalcy,” but were quickly seen as premature, and were effectively used by the same nationalist parties that had fought the war to consolidate and “legitimize” their control in peacetime.

Peter’s longstanding work with the de Borda Institute is based on his recognition that elections, as the pinnacle of collective, public decision making, are more often than not flawed due to their very structure. Put simply, why are people in “democratic” societies taught from an early age that “democracy” is simply majority rule? How is it that we have come to accept that 50% plus one is a suitable reflection of majority will, and the basis for a cohesive and functional classroom, village assembly, or state? And what better systems could help to ensure a less bipolar, over-simplified, winner/loser-based approach?

He has written numerous books, guidebooks, and articles outlining better options for not only elections and referenda, but all forms of decision making. This latest impressive book brings together his wealth of knowledge of the theory and intricacies of various election systems, with his practical experience in seeing how such systems are implemented. Most importantly, he explains how our reliance on flawed decision-making systems has brought us to a global democratic crisis.

He begins the book by providing an overview of election systems and variations, bringing a light-hearted yet informed voice to at times dense concepts, including single preference voting and various flavors of preferential voting. Following his explanation of these options, he explores the issues that many ignore: who gets to decide what options should be included on a ballot in the first place, and why have we come to accept that any such vote or referendum can only be binary, with only two options, either A or B? Instead, in a truly participatory and representative system, the process of determining a set of options to be put to a vote should be the first step, followed by the demonstration of public preference for those options.

This leads to an explanation of the de Borda count system, in which voters are able to express their preferred rankings among a set of options. Not only does this approach allow for a greater range of options to be considered, but it also helps to end the problem (experienced in particular by voters in first-past-the-post systems like the US or UK) of feeling one must be “practical” and vote for the horse most likely to win, rather than to vote their conscience. (This is an idea that is gaining traction in the US, particularly at the city level.) To use an example from a generic US presidential scenario, using a de Borda system one could note their top preference as the Green candidate, but then ensure their vote would not be “wasted” by noting the Democratic candidate as their second choice.

Following on his explanation of such basic principles, he then provides a series of chapters in which he explains how various regions and countries where he has travelled have had less than ideal “free and fair” election outcomes than might have been possible had some other system been used. In Northern Ireland, the presentation of everything as a binary option ensures continued maintenance of binary identity politics. In the UK, the limitation of the Brexit referendum to two simplistic choices not only excluded more innovative thinking about the British relationship with the EU, but also pushed citizens into two camps that were increasingly framed as not only opponents but enemies, leading to cleavages that have divided communities and even families. His review of the history of traditional approaches to voting in the Balkans explains the historical electoral dynamics that facilitated the outbreak of the wars, and then also what has constrained the peace – in particular in Bosnia. He reminds a reader that China has a much longer history of voting than many countries in “the West,” but goes on to show how simple majority-decision making has been used there for the most illiberal of ends, and has constrained any semblance of more genuinely participatory communities.

Hearing about his travels in China (cut short in 2020 due to COVID-19), I was shocked that he was able to talk about these issues there until he simply explained that he didn’t talk about voting, but community decision making. Why should some local community be forced to consider only option A (investment in a swimming pool) or B (investment in a park), when in fact people could state their preferences for both, and in addition note how they would feel about a rock climbing facility as well? It suddenly becomes easy to think about many instances in one’s own life where this kind of openness and flexibility would have resulted in a much better outcome for everyone.

A key value added of his book is that he forces the reader to question foundational assumptions. How can a broader historical sweep of participatory decision making practices be considered as countries – including in a “west” that has presumed historical ownership of democratic practice – continue to confront severe social and political trust and accountability deficits? Why is there such a desire to over-simplify issues in a way that makes us vs. then debates inevitable? And why have societies been so slow to assess how decisions are made, and to try to improve decision-making practices, starting from the local community and moving up?

While in the past detractors (including those who benefit from the polarizing status quo) might have been able to claim that such preferential approaches are too complicated to administer, that is no longer the case, as computers become more integrated into both capturing the vote and then tabulating it. Therefore the only things preventing this are voter education, and political will.

There have certainly been missed opportunities. When the election law in Bosnia and Herzegovina was being drafted a few years after the war, Peter’s preferential systems were among the models received by the OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina for consideration. Ultimately the system chosen (by the leading political parties with weak and values-free shepherding by the international community) was perhaps the worst option possible, continuing a system that not only encouraged and incentivized voting “for one’s own” nationalist party, as well as reinforcing nationalist differentiation at the expense of potential civic accountability by reaffirming the inalienable basic electoral units/districts that had been gerrymandered by ethnic cleansing in the war. Following the global financial crisis, Iceland initiated a broad public consultation on how that country’s political system could be better organized; a sweeping slate of constitutional reform recommendations was crafted yet then essentially disregarded by political parties more comfortable with maintaining a status quo they have learned how to navigate.

There is some hope that perhaps there is an opening for new thinking: Roger Hallam’s Common Sense for the 21st Century includes the use of randomly selected citizens’ assemblies (something that had been used in the Iceland process) – sortition – to begin to get closer to truly representative deliberative bodies able to change the sclerotic political system that have led to dire social trust deficits, as well as decisions that have failed to effectively address a looming climate disaster.

This book will be valuable for student of democratic processes, political science and conflict analysis. I only wish the book included more stories about Peter’s travels through the various countries and continents he describes. Being familiar with some of them from conversations, and knowing about his innate gift of being able to strike up a conversation (in multiple languages) with people in a post office or a bus station or a pizza place, such person-to-person anecdotes would be a fitting reminder that at the end of the day it is people – citizens – who are affected by and must live with the consequences of election and decision-making systems that do or do not truly ensure a meaningful voice in how decisions are made in their community or country. I very much hope that will be included in his next book.